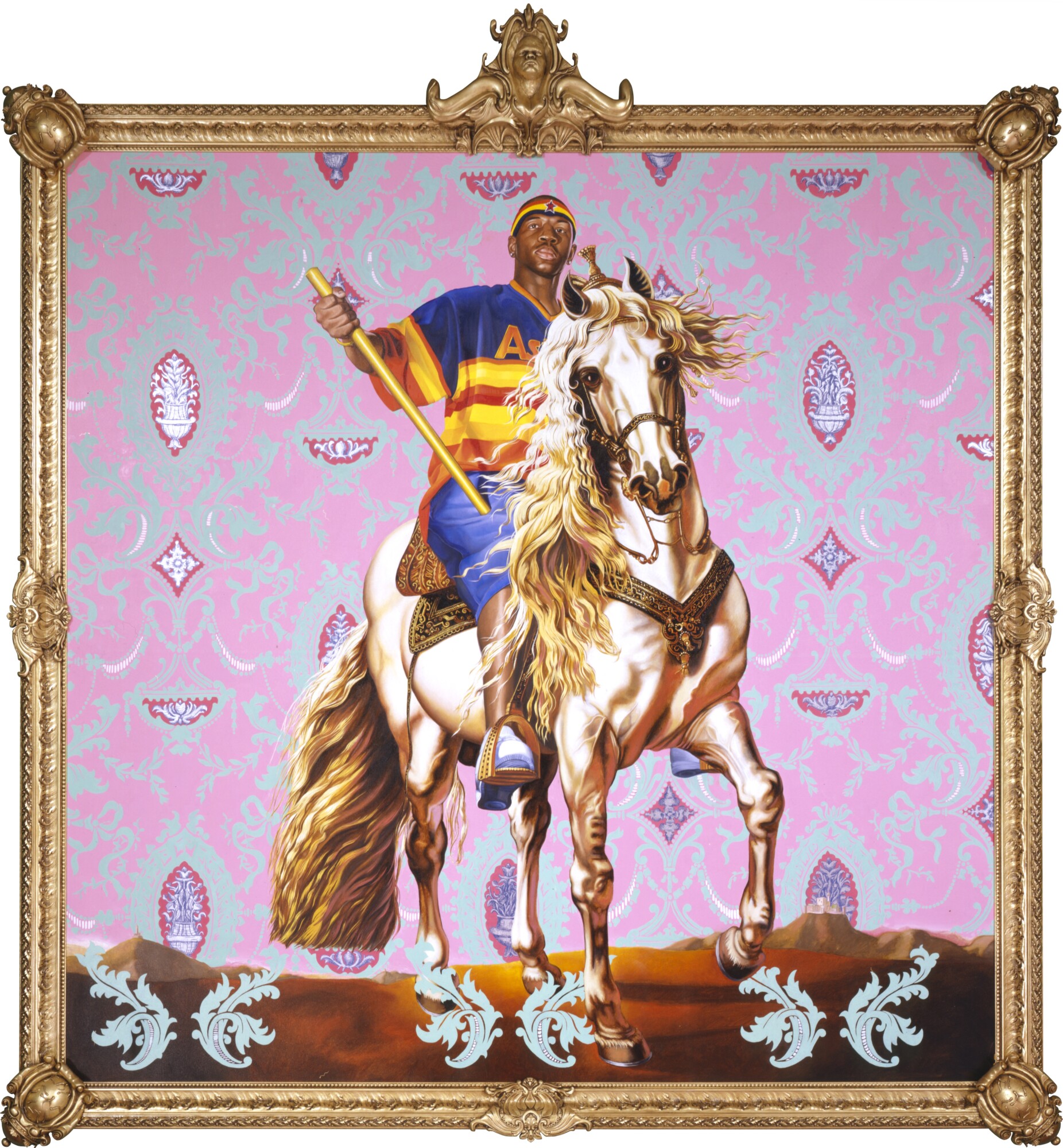

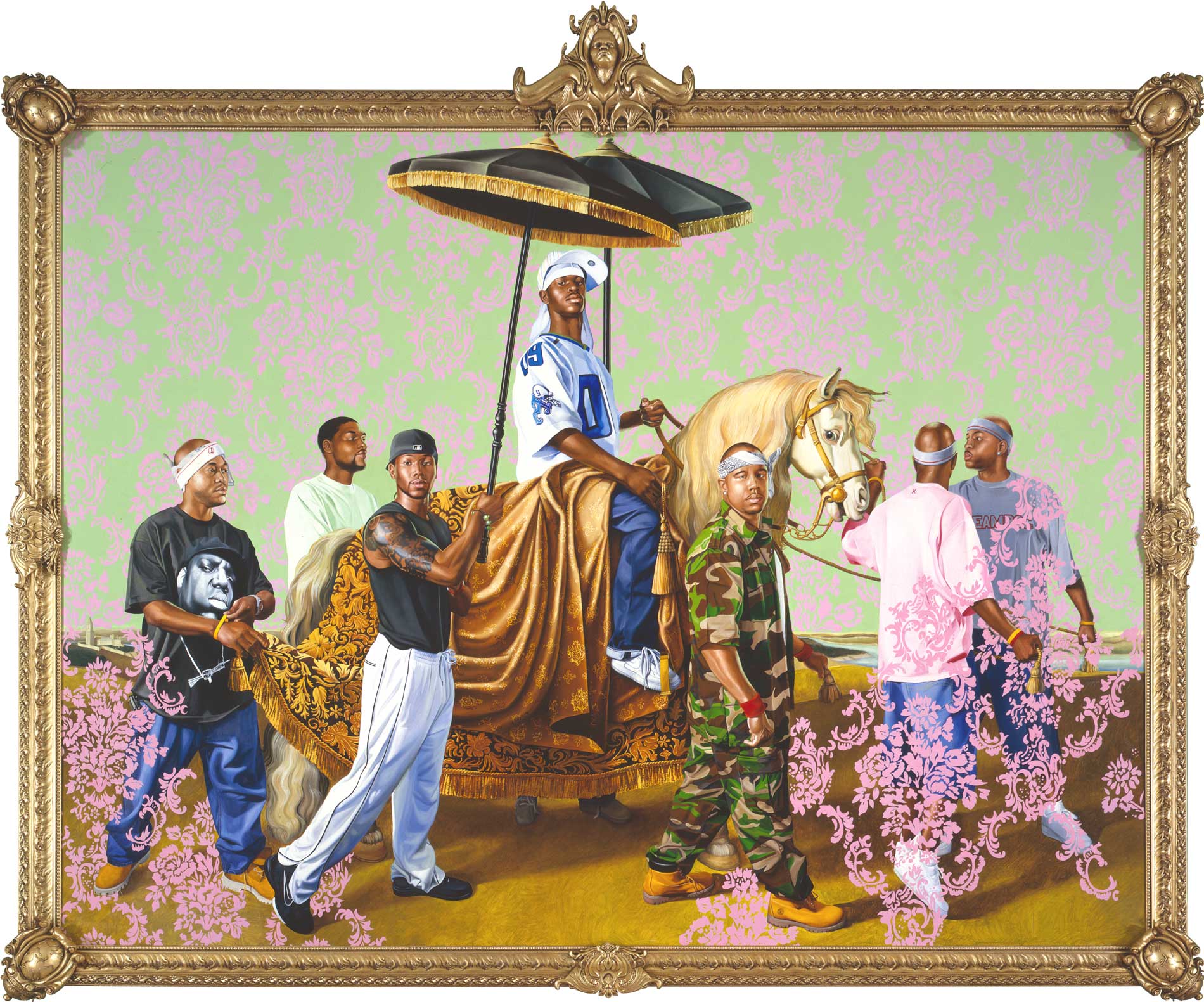

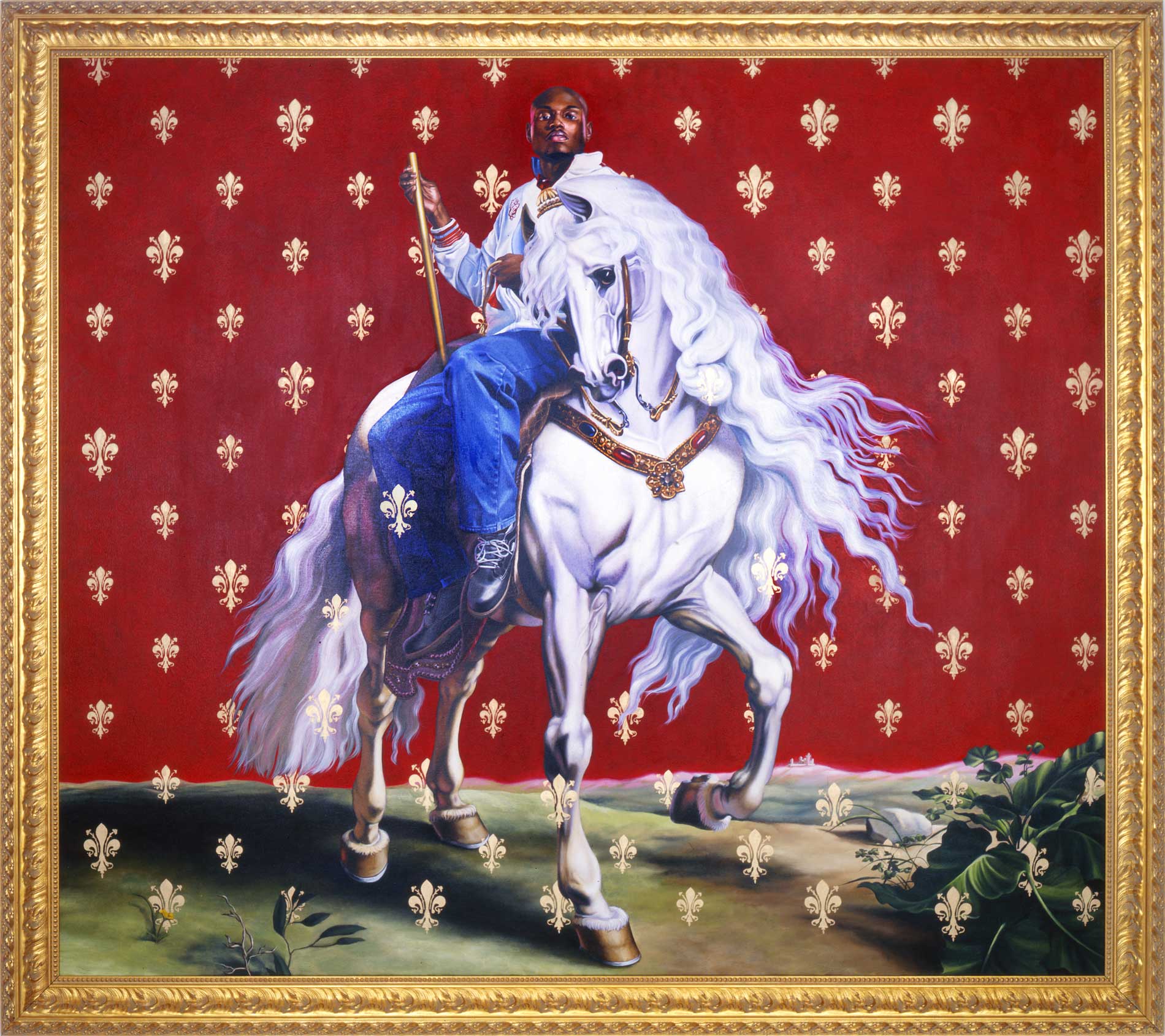

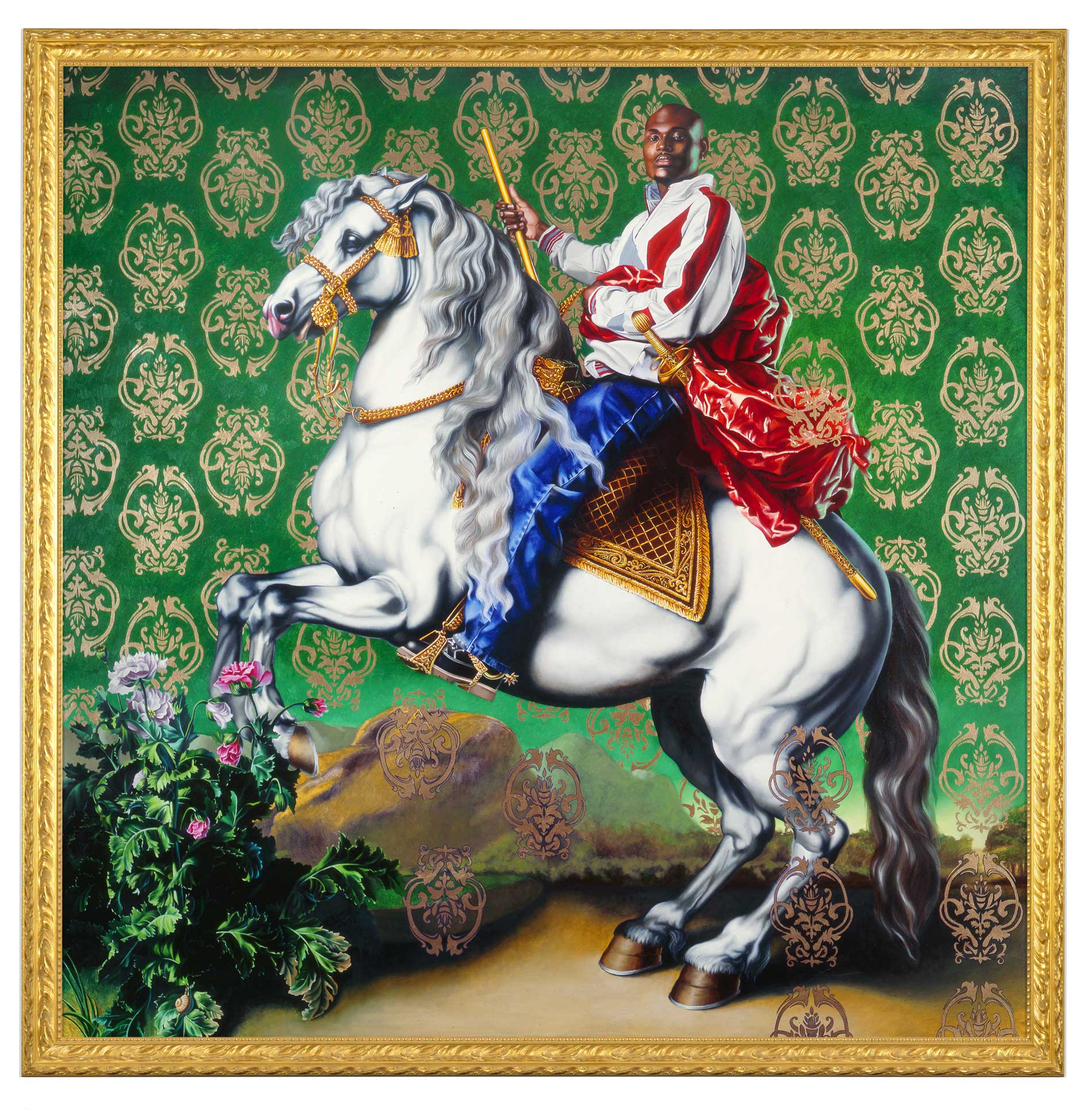

Presented by Deitch Projects, Rumors of War is a painting installation by Kehinde Wiley inspired by the history of equestrian portraiture. The installation featured four larger-than-life canvases, each updating a specific Old Master painting with a contemporary sitter, framed in custom-designed ornate, gilded frames. Soaring to heights of over nine feet, the paintings’ exaggeration of scale and high-keyed cinematic color highlighted Wiley’s interest in the aestheticization of power and masculinity.

Retaining the trappings of power implied in their sources, Wiley reproduced the rippling shoulders of thoroughbreds, the baroquely billowing fabrics, and the vague, idealized pastoral backgrounds–but instead of polished riding boots in the gilded stirrups, we find Nike High-tops. The clash of centuries and societies heightened the sense that these men were riding steeds in a charged non-space outside of time, while the extraterrestrial greens and blues of the minimal landscape pushed the surreal aspect almost to the breaking point.

The sources for the four paintings were: Velasquez’s Equestrian Portrait of the Count Duke Olivares, 1636; Charles Le Brun’ The Chancellor Seguier on Horseback, 1661; Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Leading his Army over the Alps, 1805; and Peter Paul Rubens’ Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Lerma, 1603. By reworking these historical paintings with present-day African-American, sitters, Wiley made us question the tacit racism rampant in the history of portraiture, collapsing history and style into a uniquely contemporary vision. In our present cultural moment, it seemed apt for an artist of Kehinde’s abilities and interests to take on subjects of a bellicose nature, dissecting the pomp and circumstance that went into the creation of contemporary military myths in a country at war.

Wiley described his approach as “interrogating the notion of the master painter, at once critical and complicit.” He makes figurative paintings that “quote historical sources and position young black men within that field of ‘power.’” While a stylistic shift from his 2003 Faux Real exhibition at Deitch Projects—which featured a four-canvas scuola of portraits complete with a Tiepolo-esque ceiling painting—this new body of work shared their conceptual basis while experimenting with new variables.

Wiley played with how small details often indicate, through conventions of portraiture, subtle hierarchies of power or point to hidden insights into the sitter. Throughout different centuries, the removal of a glove, a dog, a quill, bare feet, and other signifiers all had very specific meanings for the sitter of the portrait. In many different traditions of painting across borders, placement on raring horseback was often used to evoke specific military power and the virility of the subject.

The sitters for these works included people the artist met on the street, mostly from 125th Street in Harlem. They were asked to assume poses culled from the aforementioned sources, dressed in their street clothes. Wiley did not alter the style of the clothing, changing only the color and the accessories. The viewer could easily assume that the poses derived from contemporary hip-hop attitudes–where poses of dominance were also used to create a very different sort of hierarchy–as the posturing fits into the historical setting almost too well.

In an insightful essay for the brochure that accompanied Ironic Iconic, the exhibition of the 2001-2002 Artists-in-Residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Malik Gaines described how “Wiley sifts through the remnants of his culture and is able to build a whole from these many cluttering parts…With the stroke of his brush, Wiley brings his black boys to life, giving them just enough strength to contend with the terrible and beautiful pasts that continuously encroach upon all of us.”